As a longtime east-coast resident, it can be hard to admit when our neighbors to the far west get it right. But I’m all for our friends in California “one upping” us if it means they’re leading the way in helping our nation provide tens of millions of children equitable access to food!

As a longtime east-coast resident, it can be hard to admit when our neighbors to the far west get it right. But I’m all for our friends in California “one upping” us if it means they’re leading the way in helping our nation provide tens of millions of children equitable access to food!

In a monumental move, California lawmakers approved a $262 billion budget in late June that earmarks more than $700 million in funding to provide free meals to all public-school children.1 That’s $54 million for the 2021-2022 school year and another $650 million for future years.

The mere thought of what this means for the nearly nine million children under the age of 18 in California not only brings a smile to my face, but also gives me a feeling of deep gratitude. That’s because I know that, sometimes, all it takes is one small trigger to set off a seismic shift in public policy. And I firmly believe that this move may very well be the fulcrum point for universal free meals (UFM)—not just in California, but across the entire country. Even more important, it serves as a bridge that brings us together to drive positive change during what feels like a time of great divide.

Graphic: In June 2021, California approved a $262 billion budget that sets aside more $704 million in funding to provide free meals to all public-school children.1

Equitable food access is a fundamental right

This action by California is important because equitable access to food is a fundamental right, not a privilege. As human beings, we deserve to live in dignity and be free from hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition. Yet, inadequate access to fresh, healthy food persists for many people. The fight for equity means that one’s income, geographical location, employment status, race or ethnicity, and even disability should not affect his or her ability to fulfill basic human needs.

Further, research shows that sufficient access to food is an essential determinant of health—one that should not be overlooked or undervalued. What’s even more important for me, as CEO of Sodexo Schools, is the research that points to the positive impact food equity can have on children’s mood, behavior and performance in the classroom.

Data from Food Corps validates that structural inequities based on race, place and class have led to health disparities in children, particularly those of color.2 A study conducted by the organization shows that one in three U.S. kids are on track to develop diet-related illness in their lifetime. Regrettably, for children of color, it’s one in two. Further, Food Corps research shows that children who lack a quality diet are more likely to face a lifetime of challenges, including lower test scores, increased absenteeism and decreased career advancement.

Knowing this, it’s not hard to see why food equity matters so much to Californians. Of the nine million children living in the Golden State, nearly three-fourths of them are children of color.3 But California is not alone. Many states across the country are grappling with this same issue, trying to find a balance between the fundamental right to food and funding. And while the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has taken steps to help alleviate the unjust toll that food inequity can take on children for this next school year, the primary question remains the same: What are we doing to ensure long-term food equity for all children?

Equity ≠ equality

One of the cornerstones of this debate is distinguishing between equity and equality. Although the two words may seem similar, they’re quite different. According to Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University, equality means giving all individuals the same resources or opportunities, whereas equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.4 While equity and equality aren’t interchangeable, they aren’t separate goals either. Thus, we can—and should—use both to achieve equal outcomes.

Graphic: According to GWU, equality is giving everyone the same resources or opportunities, whereas equity takes each person’s circumstances into account and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.4

Graphic: According to GWU, equality is giving everyone the same resources or opportunities, whereas equity takes each person’s circumstances into account and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.4

Albert Einstein famously illustrated this concept when he said, “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” The essence of Einstein’s message is that not everyone takes the same path to success. When it comes to food equity, it’s no different. Each child has unique needs and will follow a different path to satisfy them. The goal, therefore, should be to try and achieve equal outcomes by providing just the right resources, at the right time, to the right children.

A Scholastic’s Teacher & Principal School Report focused on equity in education indicates that 87 percent of educators say their students face learning obstacles that originate outside the school environment.5 These inequities include being homeless, living in poverty and coming to school hungry. But when students’ learning and nutritional circumstances are equitable, everyone gets what they need to be successful. So, while some may argue that UFM is geared more toward equality, I believe it also advances equity by making meals more accessible to children who may need them.

COVID’s impact on food equity efforts

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the economic, racial and social inequities that exist in our world today. From high unemployment rates and wage and benefit gaps to health vulnerabilities and financial strains, the pandemic served to underscore the inequalities many people in the United States face. This is especially true for young adults, the elderly, undereducated individuals and people of color.

According to Feeding America, one of the pandemic’s most significant negative outcomes was the economic recession that brought an end to years of declining rates of food insecurity.6 According to the nonprofit organization, the pandemic severely limited financial resources for many people, which meant they simply didn’t have the money to buy sufficient food.

This year alone, Feeding America projects that 42 million people—including 13 million children—are at risk of experiencing food insecurity. And with what we know already about the racial disparities that existed pre-COVID, it probably comes as no surprise that Black individuals are nearly twice as likely to experience food insecurity as white individuals.

Given all this, what better time than now to transform this spotlight into a beacon of hope for millions of K-12 students? I firmly believe that establishing a fair and inclusive learning environment that gives kids every advantage they deserve will lead to a more equitable society. And it all starts with districts leveraging school nutrition programs to level the playing field and fight food insecurity.

A framework for food equity

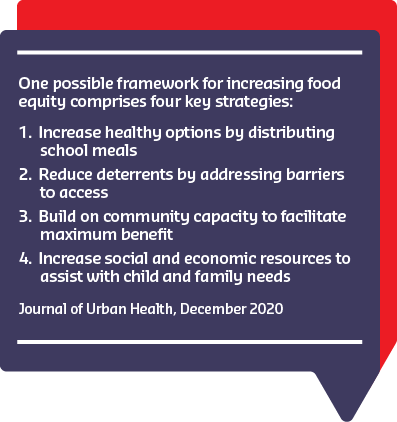

The best way to illustrate the role that schools play in food equity comes from case studies like this one published in the Journal of Urban Health, which focused on school feeding programs at four of the nation’s largest urban school districts during the pandemic. While it was intended to examine efforts to mitigate food insecurity during a crisis, I think the study provides an important framework for how districts across the country can promote equitable food access beyond COVID-19. In the study, the authors offer four strategies for ensuring food equity.7

First, they recommend districts increase healthy options by distributing school meals. For this to be successful—at least for the next school year—districts should consider ways to increase availability for fresh fruits and vegetables, such as offering a wide range of distribution locations; providing multiple meals at one time to children or their parents; and publishing menu and nutrition information.

Second, they recommend schools reduce deterrents by addressing barriers to access. This speaks to schools’ efforts to reduce the fear of discrimination or social exclusion. For example, districts can encourage participation by eliminating the need for families to meet certain income requirements. They can also provide grab-and-go meal maps, details regarding site closures, links to food banks and other resources, multilingual information, and options available for those requiring a special diet.

Third, they recommend districts build on community capacity to facilitate maximum benefit. This strategy is one of collaboration between schools and other community partners such as food banks, wellness centers, churches, first responders, healthcare professionals and police officers. This is as much about conversations as it is locations. Again, talking to the right people, at the right time, in the places of greatest need.

Lastly, they recommend that schools increase social and economic resources to assist with child and family needs. Through the partnerships described above, districts can have a significant impact on families that extends far beyond nutritional supplementation. Examples include providing access to wellness programs, technology for distance learning and improved Wi-Fi connections. When combined with better access to food, these resources can offset barriers and create more equity across the board.

Graphic: One possible framework for increasing food equity comprises four key strategies:

Graphic: One possible framework for increasing food equity comprises four key strategies:

- Increase healthy options by distributing school meals

- Reduce deterrents by addressing barriers to access

- Build on community capacity to facilitate maximum benefit

- Increase social and economic resources to assist with child and family needs

Journal of Urban Health, December 2020

Access + inclusion = a winning recipe

For all the challenges we faced during COVID, we also saw many innovations emerge that increased access to food and, thereby, created greater equity. For example, kids today have grab-and-go options that provide just-in-time access to food. “Second chance” breakfasts are ideal for students who arrive just before the bell rings and otherwise would have skipped this important meal. Children in some districts can grab a nutritious snack out of a centralized kiosk, while others may get their meals delivered directly to the classroom or curbside. These options are in addition to summer and emergency feeding programs that also fuel many students across the country.

But access to food is only part of the equity equation. The other part is inclusion. Because no two children are alike, we must remain vigilant in our efforts to use inclusive practices to help children make a connection to not only food, but also to each other.

Food creates a sense of belonging. When students see and eat familiar menu items that reflect their preferences, heritage or culture, they feel welcomed. This feeling of inclusion, coupled with diverse, flavorful menus, can be both inviting and exciting to children. When everyone has access to the same menu—without differentiation of reduced-cost or free meals that might spark socioeconomic stigma or embarrassment—there is true inclusion. It’s important to create spaces and food options that are welcoming and encourage students to enjoy their food while having fun with their friends.

I’m proud to say that Sodexo is a leader in helping build community by providing warm, inviting school lunch environments that promote continual learning and enhance health and wellbeing for students from all walks of life.

One example of this is the new foodiE Café offering that’s launching in more than 60 schools across the U.S. this fall—with more planned at the beginning of 2022. This integrated dining experience is redefining the “typical” school lunch by encouraging middle school students to explore exciting new food options while connecting with friends and creating life-long healthy eating behaviors.

What’s more, this new dining program is built with students in mind and what matters most to them: delicious food, technology that makes school lunch fun, and community connection. We’re changing how today’s middle schoolers—the most ethnically diverse group of kids ever—think about, choose and experience food. I invite you to learn more about this fast casual-style dining experience that we know students this age love, and provides them with global flavors made from fresh, local ingredients and chef-driven menus.

Food equity: The road ahead

The systemic, community, cultural and socioeconomic barriers that exist to food equity are immense. Yet, we shouldn’t let the hard work ahead of us deter us from charging forward with our efforts to create more equitable food opportunities.

It's no longer enough to simply say that we want our children to have equitable access to healthy food. It’s time to put our money where our mouth is and act. In some cases, this will require us to get comfortable with the uncomfortable task of breaking down the barriers to food equity that persist today.

Now’s the time to take the lessons learned over the past year and continue to create warm, inviting environments that are free of the stigma often associated with free and reduced meals. By doing this—and truly meeting children where they are—we’re enabling them to focus on what’s important and reach their full potential. I invite you to join in the dialogue as we work collaboratively to overcome the hurdles to food access, inclusion and, most importantly, equity. I think you’ll agree that our Gen Z and Gen Alpha children are worth our time, talent and investment in their future.

Sources

- LA Times

- Food Corps

- Children’s Defense Fund

- George Washington University

- Scholastic

- Feeding America

- National Center for Biotechnology Information